Mobilise

Sensitise

& Energise Your Hands

I teach this course regularly, so you have missed a recent workshop then please note there will be more opportunities to do a similar course or workshop in the future…

Ever since our world-wide ‘lockdown’ experience began, many movement teachers started working online. When sitting watching friends, colleagues, and collaborators inside their individual Zoom frames, you very quickly notice that some people accompany verbal speech with particularly eloquent and expressive hand gestures. I have always found hands very lovely to look at, and in my online conversations I can find myself a little bewitched as I gaze at a speaker’s hands, moving with fluid grace as they illustrate some aspect of the conversation with elegance, precision, and clarity.

Our hands are vital to our experience of being human in so many ways it would be absurd to attempt any sort of list here. Feldenkrais teachers are trained to use touch in order to teach; we learn to communicate directly with the person on our table, skeleton to skeleton, nervous system to nervous system, fascia to fascia, intelligence to intelligence. Our ability to teach effectively in this way is dependent on the sensitivity and refinement of the way we use our hands, and of course the same is true for all those who are more focussed on using touch as a healing tool in the ever-expanding field of bodywork therapies.

A little bit of neuroscience, by way of explanation…

The human hand is unique in the animal kingdom, and so central to who we are as a species that a great many of our words are derived from hand-inspired metaphors: the multiple meanings of words such as “manipulate” and “handle” can make my work as a Feldenkrais practitioner sound quite controlling! Yochanan Rywerant, one of Moshe’s original colleagues, coined the word “manipulon” to describe the way we interact with our clients in our “hands-on” Functional Integration lessons. While it would certainly make our lives as practitioners easier if we had snappier ways to describe our process, in my opinion brand new words that require lengthy explanation are not the solution. It is for this reason that I do not expect to see the word “acture” – a word coined by Moshe to evoke our dynamic relationship with gravity – to replace the word “posture” (which natural evokes an image of static position rather than constant motion) in everyday life anytime soon.

It does mean that working with our hands is as central to the Feldenkrais profession as it is for musicians, masseuses, osteopaths, chiropractors, carpenters, dressmakers, martial artists – in fact it should be obvious that any human who has hands is working with their hands to some degree.

It is not controversial to say that the pain of chronic inflammation in hands and wrists is often the result of poor self use; that the way that we are going about our regular daily activity has brought about an imbalance in the way we function as an organism, resulting in excessive “wear and tear”, and the sort of pain that makes it increasingly difficult to keep performing that particular action. The range of potential severity of this sort of injury is enormous, all the way from needing to take a couple of days off to rest, to career-destroying levels of Repetitive Strain Injury and stubborn neurological issues like Focal Dystonia.

What may not be so obvious is that a pain that you are experiencing in a very precise area of your hand or wrist is nevertheless going to require a change in your behaviour over a much wider range of activities than the one that is the most apparent cause of that pain. While your specific individual movement habits and “parasitic” muscular behaviours may take a little diagnosing by a movement expert such as a physiotherapist or a Feldenkrais practitioner, you can easily experience for yourself the kind of muscular interference I am talking about…

…try out this somewhat exaggerated version of a common form of muscular overuse:

Lift your dominant hand and twirl it in the air – you could organise your fingers as if you are playing with a sparkler at a bonfire.

Now pause, and hunch that shoulder so that it is higher than the other one (a postural habit that is common to many of us) and thus closer to your ear. Hold it there (notice how unpleasant it is to do this) and twirl your hand again – how does this action feel now?

This hunching action is not contributing to the intended movement of your hand and arm but is instead interfering with your ease of movement throughout your whole shoulder girdle and thus your whole self. Habitual muscular contractions such as these are really common; ever-present in our behaviour, yet rarely present in our self-awareness, which means they are not that easy to switch off again.

I am not exaggerating when I say that the majority of us are not experiencing the full ease and range of motion our shoulder joints are capable of, and that the unobserved restriction in our movements generated by inefficient muscular activity of this sort will eventually trigger problems that are no longer possible to ignore. Unfortunately, although we can label this unwanted muscular activity as unintentional or parasitic, the truth is that, as far as our neuronal structures are concerned, the intended action and its parasitic element are very difficult to distinguish – neurons that fire together, wire together. We have learnt to perform these two (or more) distinct actions as if they were one; they have become so habitual – that is to say we are so used to moving in this particular way – that if we are to change then we must set about the complex task of unlearning them again, a task hampered by just how automatic and compulsive these behaviours have become. In fact, as far as our neuronal networks are concerned there is no real difference between a “skill” and a “habit” – the distinction is semantic rather than scientific (something that Merleau-Ponty explores in his theories of The Phenomenology Of Embodiment).

From its beginnings Awareness Through Movement was designed to help us eliminate these mobility-limiting, energy-wasting parasitic movements. You may not be familiar with the term, but you do know the kind of thing I am talking about – perhaps you used to make some movements with your tongue or jaw as you were learning to write. This is natural, because at first we speak the words in our thoughts as we read them. Indeed we usually continue to do so unless – consciously or unconsciously – we train ourselves not to. One element of speed reading training involves learning to stop ourselves subvocalising. Moshe Feldenkrais used to demonstrate this phenomenon by getting his students to notice that they took longer to count from 11 – 20 than from 1- 10, as the numbers are shorter they take less time to “think through” – you can easily try this for yourself if you are curious.

If you would like to understand more about the concept of parasitic movement and how “neurons that fire together, wire together” I can recommend Mind Sculpture by Ian Robertson as a discussion of how the brain functions that is both clear and elegant.

I am sometimes wary of recommending books written by Dr Moshe Feldenkrais himself – his prose is easier to read if you are familiar with the rhythms of his speech, but The Potent Self is my favourite, and also I think perhaps the best book to begin with if you are interested in the widest applications of the Feldenkrais Method. In this book he broadens his discussions of neuroscience to include the emotions, and the limitations of compulsive behaviour:

– and if you are not feeling overloaded at this point and are interested in a more academic exploration of the relationship between skills and habits in the learning process, then you might like to check out artificial intelligence expert Hubert Dreyfus, on YouTube or in print – The Current Relevance of Merleau-Ponty’s Phenomenology of Embodiment– don’t be put off by the title, both the article and the videos are great fun, if a little long…

Several of my workshops explore these themes, and details of my upcoming workshops are on my dedicated blog page here.

…a little more neuroscience, on the subject of sensitivity…

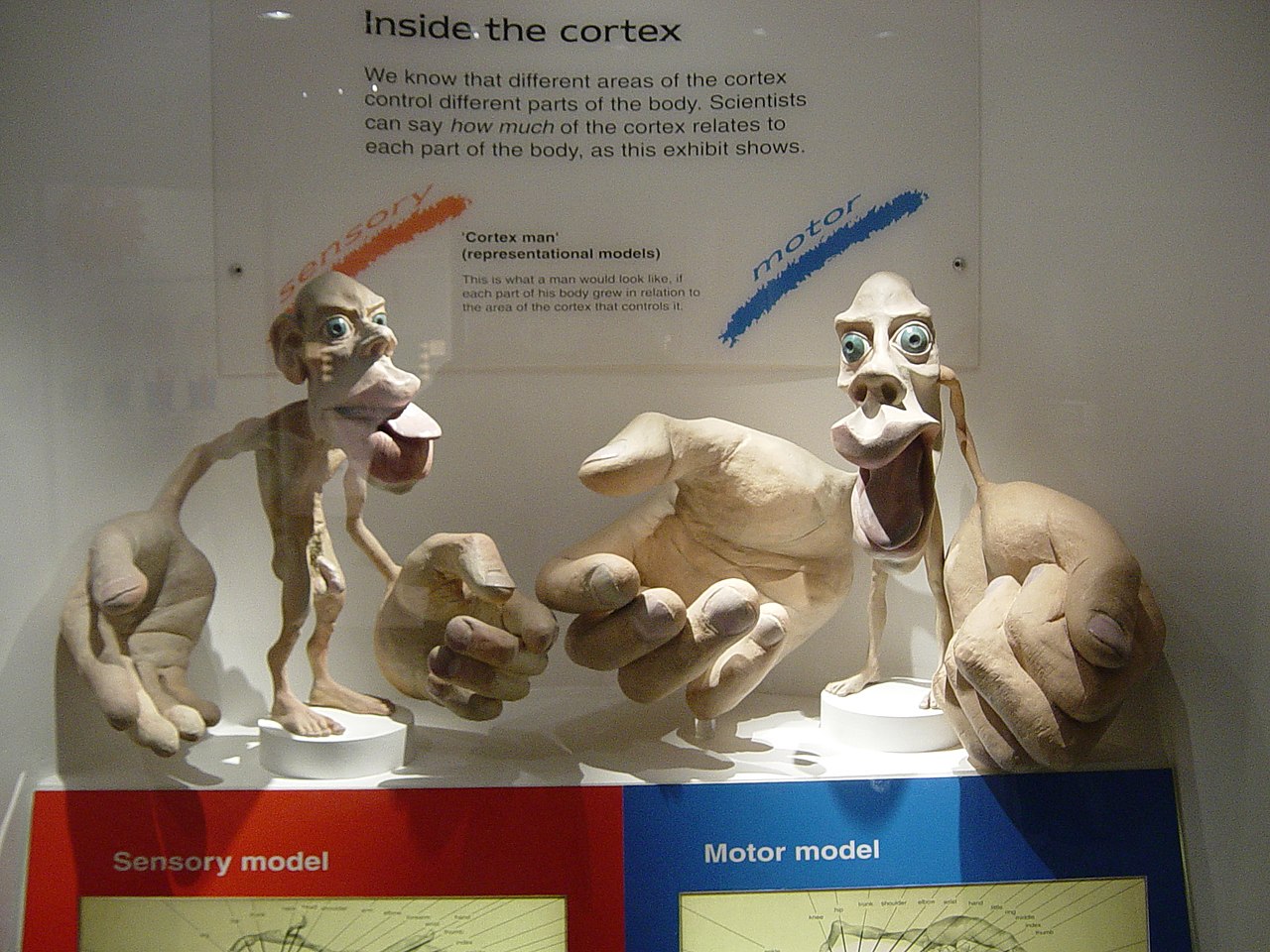

“As with the Sensory Homunculus, the Motor Homunculus looks distorted. For example the thumb, which is used in thousands of complex activities, appears much larger than the thigh, with its relatively simple movement possibilities. The Motor Homunculus develops over time and differs from one person to the next. The hand in the brain of an infant is different to the hand in the brain of a concert pianist, which is different again to the hand of an adult who doesn’t play an instrument.”

…as you can see in the image that accompanies this article.

Moshe Feldenkrais used his pioneering recognition of our life-long neuroplasticity to create a whole series of lessons designed to speed up our ability to change bad habits into better ones.

Bookings and enquiries – contact me here

Original :Taking Good Care Of Our Hands; publ. 3.2.14