The Feldenkrais Method is all about enabling, supporting, generating, enhancing, and encouraging life-long human self-development, both for the individuals who adopt it as a practice, and potentially for human society itself, because the processes we engage in are so fundamental to understanding ourselves better as creatures.

This makes our Method somewhat difficult to pin down in a few words, and it also means that those of us who teach these carefully-honed strategies for self-awareness and self-integration are well aware that we are also still learning more about the process itself, even as we persevere with teaching others. For most Feldenkrais practitioners our professional goal is to foster a continuous state of learning and self-maturation within ourselves as well as for our students.

Such a bold aim is only possible thanks to the way our highly-evolved human bio-system works; we are not only ‘neuroplastic’ – i.e. capable of changing our brain’s wiring by changing our behaviours at any age, as Norman Doidge has explained so eloquently in two major books so far…

“After the initial critical learning period of youth is over, the areas of the brain that need to be ‘turned on’ to allow enhanced, long lasting learning can only be activated when something important, surprising, or novel occurs, or if we make the effort to pay close attention.“

Norman Doidge –The Brain That Changes Itself; 2007 [Italics mine]

…but also “bioplastic”, which means that – with enough commitment to change – we can reverse much of what is generally represented as the ‘inevitable’ deterioration that comes with age, if not always with regard to our physical appearance, then certainly in how we move, sense, think, and feel.

The term “bioplasticity” has been adopted and popularised by the ‘bio-neers’ at the leading edge of the current research into chronic pain. If my statement sounds like an exaggeration then just take a moment to read a nice long list of the improvements to physical functioning the human bio-system is capable of achieving.

The full potential of our potential for change is only just beginning to be recognised. Medical science is not the most effective forum for exploring these possibiites; it is not controversial to point out how little money there is to be made out of the sort of thing that undoubtedly works. Of course that does not stop big business doing its best to monetise diet and exercise, nevertheless much of what we can do to “rejuvenate” ourselves involves lifestyle changes that begin to reverse the damage we have done to ourselves only slowly, and any particular intervention we try will usually require careful calibration to our own individual needs.

The Feldenkrais community is engaged in developing the science of learning, and as such is a more suitable subject for the observational processes that can be gathered under the heading of “Phenomenology”. Indeed, Feldenkrais could be described as a training in personal and interpersonal phenomenology:

Here’s a full definition…

“Phenomenology is the study of structures of consciousness as experienced from the first-person point of view … The discipline of phenomenology may be defined initially as the study of structures of experience, or consciousness. Literally, phenomenology is the study of “phenomena”: appearances of things, or things as they appear in our experience, or the ways we experience things, thus the meanings things have in our experience. Phenomenology studies conscious experience as experienced from the subjective or first person point of view.

Someone – sadly I cannot for the moment remember who – described Feldenkrais as a ‘philosophy of movement’. In my opinion that isn’t quite it, although it comes close, and matches the way it is often perceived. I think it is much clearer to describe it as a ‘philosophy of learning’ – an ever-evolving system for learning how to learn; a system which certainly does lean heavily on the dominance of movement-related neuronal structures in the human brain for the effectiveness of its techniques – and, also of course, for the fun. As a system based on the way humans learn best, the vital importance of playfulness in our development process cannot be overestimated, and it is a fundamental element of successful Awareness Through Movement lessons, which is why we often end up rolling, or wriggling, or bouncing when we get up off the floor and walk around at the end of the lesson.

Most of us have no trouble applying the concept of learning to the process by which we become able to speak another language, play an instrument, or master a computer programme. It isn’t controversial to talk about learning to speak, and to walk, even though we do not usually remember doing so. I have some memories of being taught to tell the time, but none of any significance about learning to read. I do clearly remember chanting my times tables out loud with my classmates, and still sometimes find myself calling them up again 53 years later. It is well understood that, in the first years of our lives, as we move through our various developmental stages, much of what we learn seems to be absorbed quite naturally and effortlessly in an ongoing process of self-integration.

As adults it makes sense that we remember best learning those skills and abilities that we were required to practice through repetition and testing. It becomes more complicated once we start to examine the huge amount of material we processed and integrated into our brain/nervous systems via our multiple interoceptive and exteroceptive senses. As babies we each also learned to distinguish what we could see, hear, smell, and taste, and to handle materials of all sorts… and not only that…

…We steadily acquired the necessary abilities for our survival, and growth…

We learn about gravity directly through the ongoing refinement of balancing our heavy skull over our short, stubby legs.

We learned about friction, and heat, and cold, and love, and fear – long before we were able to frame those concepts in the language that we were acquiring simultaneously, at an astonishing (but very individual) rate.

Most significantly, as very small babies we begin to ‘prune’ away those sensory sensitivities we do not seem to need for our immediate survival in the environment we find ourselves born into. This is an exciting, still poorly recognised aspect of our individual child development, however any full explanation would require a couple of thousand words, and I am trying to stay on track. I will return to the subject of our inborn hyper-sensitivities, and our early sensory pruning process in a follow-up article. All I want to suggest at this point is that some of this subconscious sensory self-management can be brought into our conscious awareness, with many potential benefits for our health.

Learning to learn to be well…

Feldenkrais can change your life. Some people “get it” straight away, and those people often go on to become my colleagues. Others come along to classes and workshops regularly, and have the odd hands-on lesson every few months, but never quite make the shift into the self-generated self-development process the Method was designed to instill. Of course there are many reasons for this; modern life is busy, most of us already have an awful lot to do, and it isn’t so easy to make time for more of something, even when we know that something is changing our daily life for the better.

Stories of miraculous “breakthroughs” are more exciting for the reader, and consequently more appealing to the media – plus, they hold out the hope for an easy solution to our problems. Real change of the sort that permanently improves our well-being usually requires regular – often daily – practice, and so, without the immersive experience of a professional training, many people are only skimming the surface of what Feldenkrais is capable of achieving.

Added to that, our potential for continuing self-development is poorly understood; our culture is riddled with out-of-date ideas about human capabilities, constantly pushing the “nature” side of the story at the expense of the more empowering “nurture” pole of the human equation. As soon as I began to understand how much we are shaped by our experiences from birth it became obvious that genes could not be the determining factor that they are often portrayed as being, despite the popularity of reductionist concepts such as the metaphor of the “selfish” gene.

As long as there is money to be made by pushing the genetic determinism narrative there will be less interest in just how adaptive, responsive and capable of new learning our sensory-motor-nervous systems can be. Our current model of healthcare treats us like machines in need of fixing, rather than self-healing bio-systems, fully capable of bringing ourselves back into balance with the right sorts of shifts in behaviour.

No wonder we are struggling to heal our planet when our ideas about how healing happens are based on such limited and inaccurate reductionist models. We live in a world where the wealthy fantasise about extending their lives by replacing a brain and nervous system at the pinnacle of evolution with mechanical (and thus ‘patently’ non-self-healing) bodies: bodies into which they believe they will be able to download their consciousness, despite it being very clear that neuroscience still has absolutely no explanation for what consciousness is, or how we came to have so much of it.

My own physical condition improved during my very first experience of an Awareness Through Movement workshop, but I didn’t know why – and I did not realise how profoundly it was going to change my life either. Even after four years of training and 33 years of teaching my understanding of this deeply human “art” continues to grow, pretty much on a daily basis.

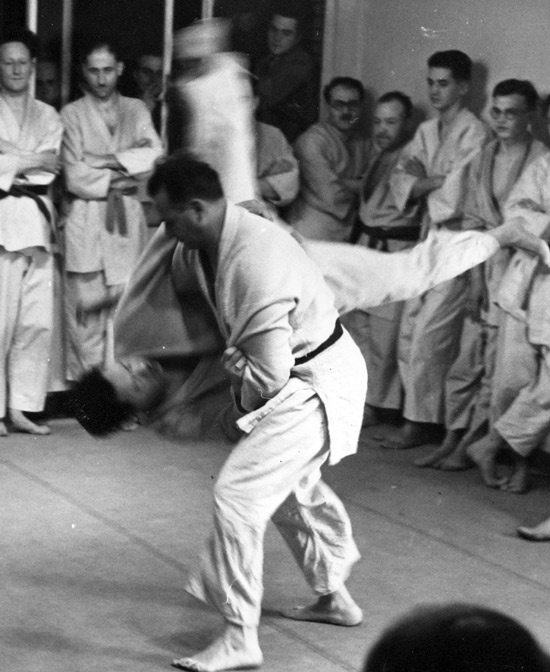

One thing has become clear; if my more casual students are to get more of the potential benefits of “learning to learn”, then clarifying what constitutes a daily Feldenkrais practice is crucial. No one imagines they will become a Judo or Tai Chi master with a weekly class and an occasional 30 minutes practice at home. No one who considers themselves to be “doing” yoga, or Aikido, actually believes that an hour a week is enough to reap the potential benefits of these wonderful systems.

The Feldenkrais Method suffers from the very size of its founder’s ambition. It sems clear to me that Moshe Feldenkrais was designing an updated form of Ju-Jitsu – Judo 3.0 – an intentionally non-martial human development art, something suitable for a peaceful, modern, densely urban global culture; a selection of skills easily adaptable to the 21st Century and beyond; a training manual for maturing and fine-tuning the human nervous system, so that any one of us, of any age, could – in time – become capable of upgrading ourselves whenever and however necessary, so as to be ready – and eager – for any new experience that comes our way.

Feldenkrais intended his Method to become a constantly evolving meta-learning process. He believed that he could refine the most effective elements of learning-how-to-learn, so that his students would be able master anything that they set out to; not just physical skills, but mental abilities as well – ultimately his aim was that a person who studied his method would be free to choose any life path that called to them. He talked about returning us to our “full human dignity”, and helping us achieve both our “avowed and un-avowed” dreams. It frustrates me a little that when you read much of what is written about the Method you might actually think that the goal is merely being able to move with more ease – Moshe would bellow at his trainee teachers, “It’s not about rolling! Any idiot can roll!” (I am paraphrasing, but when I have more time I will locate and share a direct quote).

It is sometimes claimed that Feldenkrais was reluctant to engage with the subject of human emotions; nothing could be further from the truth. We as a community are lucky to have many hours of recordings of Moshe’s final practitioner training, and his many lectures on a huge variety of related subjects are still inspiring our community to this day. This training took place in the US, at Amherst in Massachusetts. In Awareness Through Movement, Moshe had written:

“The aggressive impulse has always been the stumbling block in the way of Man’s attempts to improve himself. A few exceptional men who really sought peace and true brotherly love reached this condition by perfecting their awareness, not by suppressing their passions.”

Awareness Through Movement: Health Exercises For Personal Growth;

Feldenkrais, Moshe, 1972

At Amherst he refined this idea more precisely: he begins by referencing a letter he has received from a woman who had witness her mother being killed in front of her by members of a fascist organisation. The writer says that she hopes she will in time ‘forget’, and become able to while remain calm while listening to discussions of terrible experiences of this sort. Moshe says*:

“Well, I am against forgetting. I believe you shouldn’t forget that somebody killed your mother in front of you… [except that] this has nothing to do with Capitalism, or Fascism because… in Russia, in Siberia, there are mothers seeing their sons dying from years in prison for no fault at all… no “ism” is responsible for that.

It has nothing to do with any organisation, it is a general human fault, and unless this is corrected you should never forget it!

We must distinguish very clearly. Aggression is one of the most important ingredients of the human character, and it is essential – so if it weren’t aggressive we wouldn’t do anything. We are aggressive when we bite an apple, we are aggressive when we kill a chicken … but an extraordinary difference is when you achieve your aggression with violence – and people mix up violence with aggression… Gandhi was terribly aggressive [because he wanted to change the world towards his way of living]… Aggression has many many faces … You couldn’t live a single day without aggression – but we could live a lifetime without violence, and, as people do not distinguish between those things, they actually fight against aggression and therefore make it impossible for people to accept it.That’s why aggression was always flourishing – because they were fighting against violence – using violence to fight violence – and therefore how can you get anywhere with that? It’s idiotic.

Now, unless we distinguish between those two things and educate generations to understand that aggression is the most important thing in life, and that violence is not necessary to achieve anything. In fact it hinders; it interferes with achieving anything…

Alright now, we finish with that I hope for now – not forever! – because this is a kind of re-education of oneself and the people around you that must be achieved if we one day won’t have mothers being killed in front of their children, or any other violence of that sort. …But it is nothing to do with the “isms”! – whatever they are…

Alright, now … Would you please stop being serious!” – and he returns to the subject of the wonderful week of learning they all have ahead of them.[Later he adds that it is people’s way of organising themselves that leads to violence. Their inability to feel good internally causes them to use violence to accomplish their goals.]

Transcribed from the Amherst recording for AM, June 29th, 1981, with additional material from the Amherst Training notes of Tommie St. Cyr

*You can tell Moshe was indeed a passionate man, as you might expect from someone who switched so easily in his writing back and forth between pioneering neuroscience, and ideas about human dignity and achieving the the deepest dreams of our hearts. He also speaks with great passion, and when reading his words it can be helpful to have a sense of his rhythm and intonation, so I have chosen this short talk for those of you who have never heard him speaking – have a listen, and then read his words again, and you may find his style of lecturing easier to comprehend.

My goal as a teacher is to find as many ways as possible to make it easier for you all to do some Feldenkrais every day.

I have online classes, weekend workshops, and daily 90 minute immersion courses, and I also teach one-to-one sessions online, in both Functional Integration, and Potent Voice.

I know from experience that it is possible to use this body of learning strategies to keep coming up with new ways to make my own life a little better, one behavioural shift at a time. Some of these strategies are particularly suited to daily practice, and I am steadily organising them into a format that will work in a similar way to a Tai Chi or Qi Gong form, so that it will be easier to do a little Feldenkrais every day, and thus to follow your unique path to your own “avowed and unavowed dreams”.

Hi Maggy,

I have read quite a lot of what you have written in your website and I congratulate you for the effort and intensity you have put into it.

I am currently recovering from a fractured vertebrae and constantly searching for a way to overcome the tactical allodynia the incident has left me with.

I read a book by Dr Jill Bolte-Taylor called “My Stroke of Insight” literally a couple of weeks prior to my accident and I am certain that this is the only reason I am now able to walk because I knew that not only does the brain talk to the body but the body also tallks to the brain through movement.

The consultant who performed the surgery told me to get used to the idea that I would be wheelchair bound from then on due to the severity of the damage to my spinal chord but I would not accept it.

The physiotherapists thought I was perhaps in denial when I asked for a loop to put over my feet so I could pull each leg towards me in turn, several times a day and try to push against it.

They acquiesced regardless and for the next 3 weeks I practiced this movement in 10 minute blocks, several times per day. It was agony but they started getting excited in the 3rd week when I was able to show them the legs pushing against the loop.

By the end of the first month I was able to walk again (sort of) and they were amazed but I knew it would be so.

As such I have developed a huge appetite for learning about the brain and how it can change and adapt through plasticity, prompting me to read Norman Doidge’s book “The Brain’s Way of Healing” in which he speaks a lot about Moshe Feldencrais.

I have been in contact with Dr Taylor and she attributes her recovery to him.

Anyway, long story I know but I just wanted you to know how much I have appreciated your effort.

I only wish you were closer because I live in St Ives Cambridgeshire which is a bit of a hike to London and I am not too sure about the idea of zoom consultations.

I am convinced though that this is the key to unlocking my constant misery so I may just give it a try.

This is not something I want to begin just yet though as I wouldn’t not be able to give it the time comment that it must have to be effective.

I will however make it my plan to listen in on the upcoming lecture series in May.

Best regards

Carl

Apologies for taking so long to respond – I have sent you an email.

Best wishes,

Maggy